The Humans in the Loop: Labor Exploitation and AI Training

Attempting a self-experiment.

This article is a student preprint that has not undergone a scientific peer review process. The content represents an independent scientific discussion, but does not claim to be conclusively valid or completely free of errors. Particular caution should therefore be exercised when using it for scientific purposes or citing it.

Disclaimer: AI was used during the creation of this post in multiple ways and forms. I am aware of the use of AI can inflict explosive labor practices and a high carbon footprint. For further information on the ecological consequences of high data usage please see Rafaels post in the same blog. For more information on the possible labor exploitation in AI please continue reading.

Legal statement: Due to data disclosing restrictions, no actual task data will be published - only example training data will be shared to illustrate possible tasks. In addition, companies (except for Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT)) with which I conduct experiments will be anonymized in the parts regarding the experiment (in literature cited companies will be named). Every similarity to real project data is by coincidence.

The Human in the Loop: Machines Exploit Humans?

Artificial Intelligence (AI), such as the widely known and popular ChatGPT, a large language model, needs data - a lot of it. Especially during their training phase. The better structured or annotated the training data is, the better the AI results. So how is this data annotated? Or rather by whom?

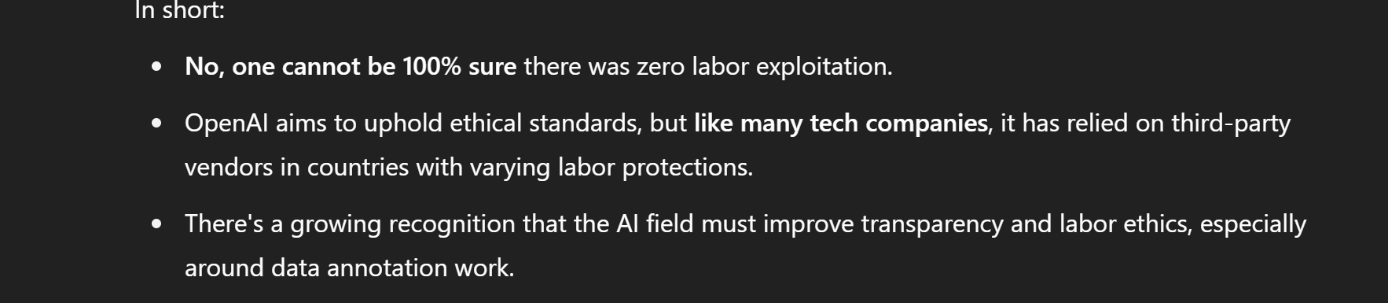

If you ask ChatGPT directly about the labor condition during the training data annotation process for itself1

Surprisingly enough, quite a big part of it is handmade. Just as a large portion of our clothing is produced in sweatshops, a significant part of data is annotated in tall, windowless concrete buildings, by people who must work 12h shifts and early literarily pennies for it.2 Not all data is annotated under such circumstances. Data annotation projects can also be a remote and flexible option, as all the companies promise, for a side income conducted by highly qualified personnel.

However, the sheer amount of data that systems like ChatGPT require, and the massive volume of data produced under exploitive conditions, creates a situation where I would argue that most larg AI systems include annotated data from exploitative environments. This structural exploitation is part of what is often referred as “black box” in AI algorithms and is often not actively perceived when “intelligent machines” answer our questions in seemingly magical ways. Maybe there is more human in AI than we often assume.

So far, the argument of this post has not fully been explained. Is the goal just another guilt trip to convince readers to not use AI anymore? Not entirly, even though there are good reasons to use it less or at least more thoughtfully (see the other articles of this blog).

There are many industries based on labor exploitation. For example the raw materials used in technological hardware like smartphones and laptops. Isolating data annotation would mean removing it from a global system of exploitation. The goal of this post is to shed light on how much human labor and under what conditions is embedded in “basic” AI training - and to discuss some alternative possibilities for crowdsourcing data for projects.

Therefore, the target audience includes both an interested public as well as researchers, concerned with data sourcing or data ethics.

A second element of this post is a self-experiment: “working” as a tagger and reflecting on that experience. As you will see, working might be a somewhat exaggerated term in this context. The parts that include my own experience are marked in italics. I decided to try this experiment because I wanted to experience how data annotation work feels like.

To some extent, this would be comparable to the methodology of participant observation used in ethnography. However, it is important to consider one’s own positionality. To put it bluntly, I am writing from a privileged position. I do not depend mainly on my income as a tagger, I can stop whenever I want, I don’t have to be constantly afraid that my account will be locked, I have alternative job options. Which results in valuing this work opportunity in general differently.

Considering those differences, what benefit does the experiment offer? Even though I can’t experience the full scope of exploitation, it still may deepen my understanding of the system and tasks involved. This may help to imagine alternatives for non-exploitive crowdsourcing systems.

Sunday Afternoon: Trying to sign in as a tagger. First issues.

When you opened the website of one of the remote work platforms the first thing that you see are sentences like: “Join a global community of over [several hundred thousand] Taskers”, “Do tasks, get paid. It’s that simple. Start earning today.” or “Work from anywhere, anytime.”. Intrigued by those promises, I tried to sign up for the platform.

However, …

Working from anywhere? Not if you are in an unavailable country. Not even the unavailable graphic was depicted properly.

The first issue I had was my location. The platform seemed not to allow sign-ups from everywhere. While trying to find out how to overcome that hurdle, I found that my region was not the only one that was affected. Remote platforms seemed to pull back from different regions. One example is Remotask in 2024 pulling back from Kenia, Nigeria and Pakistan and halting new sing ups in Thailand, Vietnam and Poland.3 Remotask also has a working location policy especially for if you are working on Generative AI projects. Those projects are only available in limited countries, and you may be required to provide your government issued ID to ensure your location. In case you change your primary country, you are as well required to provide to update your location, if not your account may be paused.4 Sounds a bit like as the promised remote freedom changes to a remote-control relationship. The reason for those kind of policies, Remotask isn’t the only remote platform having those, maybe related to the attempt of AI regulations on some regions as for example the EU AI Act.5

However, back to my own experience. Since the website I wanted to try out seemed to check the location of my IP address, I tried to change it, however neither Japan, the Nederland nor the US worked. Sometimes I got redirected to a different platform and try working there. I already knew the company from an Instagram commercial.

Later I released the two platforms seemed to be connected. Both seem to be subcompanies of the same company providing data for AI models arguing “to powers nearly every major foundation model” and bragging to have “pioneered in the data labeling industry by combining AI-based techniques with human-in-the-loop, delivering labeled data at unprecedented quality, scalability, and efficiency.” Something that sounds to me already comically evil in the context of my topic.

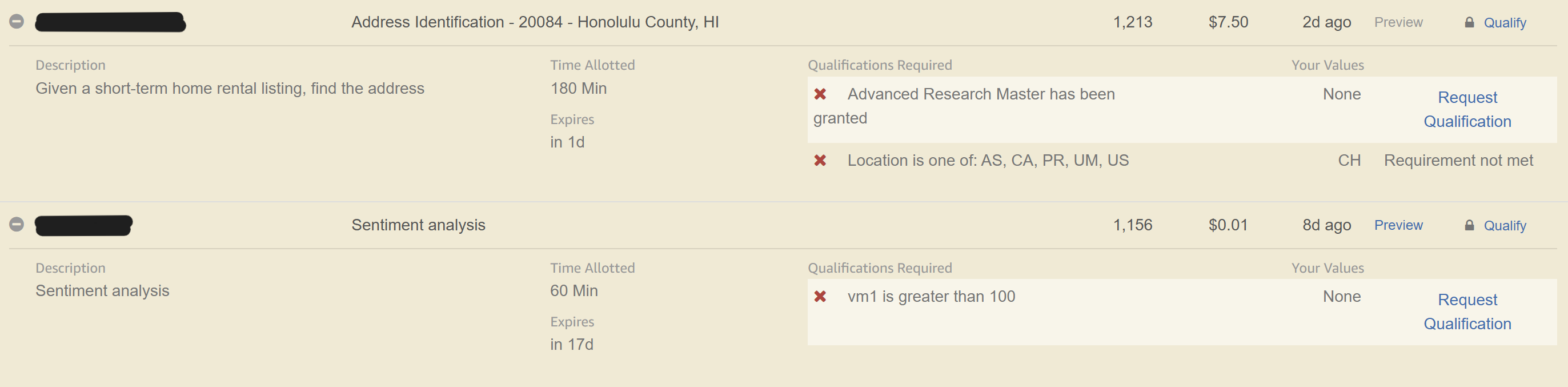

Since the first platform did not work, I decided to try a second platform, this time Amazons Mechanical Turks (AMT), one of the first large crowd sourcing platforms. The system is pretty simple employers advertise tasks, and workers complete tasks to earn some money. Employes can define filter, for example skills or based region.

Example tasks. Rewards are granted by task and as you can see the amount can greatly differ. On this day the max amount was 8$ for an allotted time of 30min. Screenshot taken on the 29.05.2025.

Luckly, I could sign in as a worker; however, my account first had to be reviewed before I could start. While browsing already tasks, I realized a different issue. For most of the tasks you had to be based in an English-speaking country like the US. Therefore, I created a second account, seemingly based in the US. The next step was to wait to be approved…

Labor Rights and AI Training

In a report by Amnesty International in 2024 about the situation of laborers working on data annotation mostly for AI in the Philippines, several concerns regarding labor rights are mentioned. First, workers are considered subcontractors and are therefore responsible for themselves. The issue, however, is that they are often not independent but have a “boss, office hour and even a scheduled lunchbreak”. Even if they work independently, they sometimes must work up to 12h a day, seven days a week for as little as $8. The reason is that taskers are often not paid by hour but by task. In addition, workers don’t have any work contracts and no social or health insurance. This system works mainly in regions where there are no or only a few not criminalized income perspectives. 6 Sometimes, self-exploitation in AI annotation is one of the only ways to earn a legal income or have a professional perspective. However, this fact alone makes it not less exploitive. In this context, also the often-positive notion of remote work - “working anywhere, anytime” -takes on a different meaning, as taskers are placed in a global competitive field against each other, lowering the prices for their work.

In this system of global anonymity, workers are highly vulnerable to requesters and platforms, bearing the largest share of the individual risk. As Gray and Suri show in their book Ghost Work (2019), workers accounts can be blocked and closed with no warning and almost no possibility to apply for a case review.7 I experienced something similar when opening an AMT account. Additionally, platforms may have bugs, that cause your work is getting flagged for no reason, which may result in warnings, fewer task options, or even a banned account. For a system this is a malfunction. For a requestor, it might be a nuisance. But for a worker, it can mean the loss of income and economic insecurity. Therefore, workers are under constant pressure to deliver, while never being a 100% sure that their account won’t be blocked due to bad feedback or a mistake.

Some platforms have whistleblower websites and hotlines, where workers can make anonymous reports or as the website calls itself “comprehensive ethics reporting hotlines”. According to their description their line of duty reaches from general HR topics to workplace harassment and discrimination, fraud, and other code of conduct initiatives” and their provide their service to a similar wide range of industries, from Not-for-profit organization to Financial services and from technology to construction.8 Whereas I think it is a positive remark that reports and concerns can be submitted anonymous and that they could be a way for workers to defend themself, those hotlines seemed to me judged by their web-appearance, equally concerned with ethical reporting as with legal concerns of companies. In addition, their scope does not seem to directly contain task-related issues. A further investigation into their possible impact on labor rights and their scope could be interesting.

Nevertheless, the power dynamics, as well as the scope of action of its players in this system, stay so far highly unequal.

Monday Afternoon: Am I too privileged to be exploited?

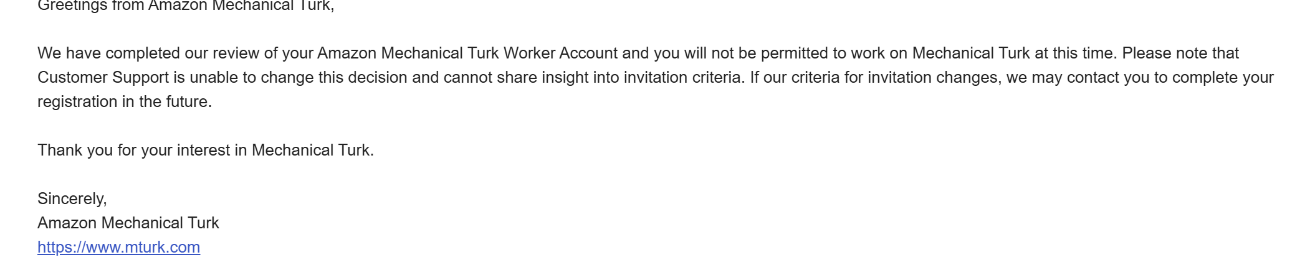

The reason why I am naming Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT) platform instead of anonymizing it like the others is that I never even had the chance to start with a task nor even training for one. Since the day after registering, I received the follwing email from Amazon regarding my application (for my Swiss based account)

I was “not permitted to work on Mechanical Turk at this time,” and for the moment, that decision could not be changed. I could not gather insight into the reasons why I was not permitted. When logging into my AMT worker account the pop up appeared telling me soly that they where unable to extend an invitation to every newly signed worker and that they will notify me “should conditions change in the future”. A bit later, I received the same email also for my US-based account.

What a bummer. Could it be that my experiment already end at this point? Was it not even possible for me to start one task?

There are options to buy post-reviewed accounts of some remote work platforms, which are accepted and have already gone through the training process, sometimes they are advertised on social media for up to 200$ as far as I saw. The other solution would be to ask a proxy for help. However, if this person also works on the same platform, they may risk getting flagged.

Alas, I had a different idea. I tried to sign up for the first platform again, but this time relocated (at least virtually) to the Philippines. I choose the Philippines because of the already mentioned article by Amnesty International about the labor conditions in the tagging factories there. And look at it - it worked! I was able to sign in and create an account.

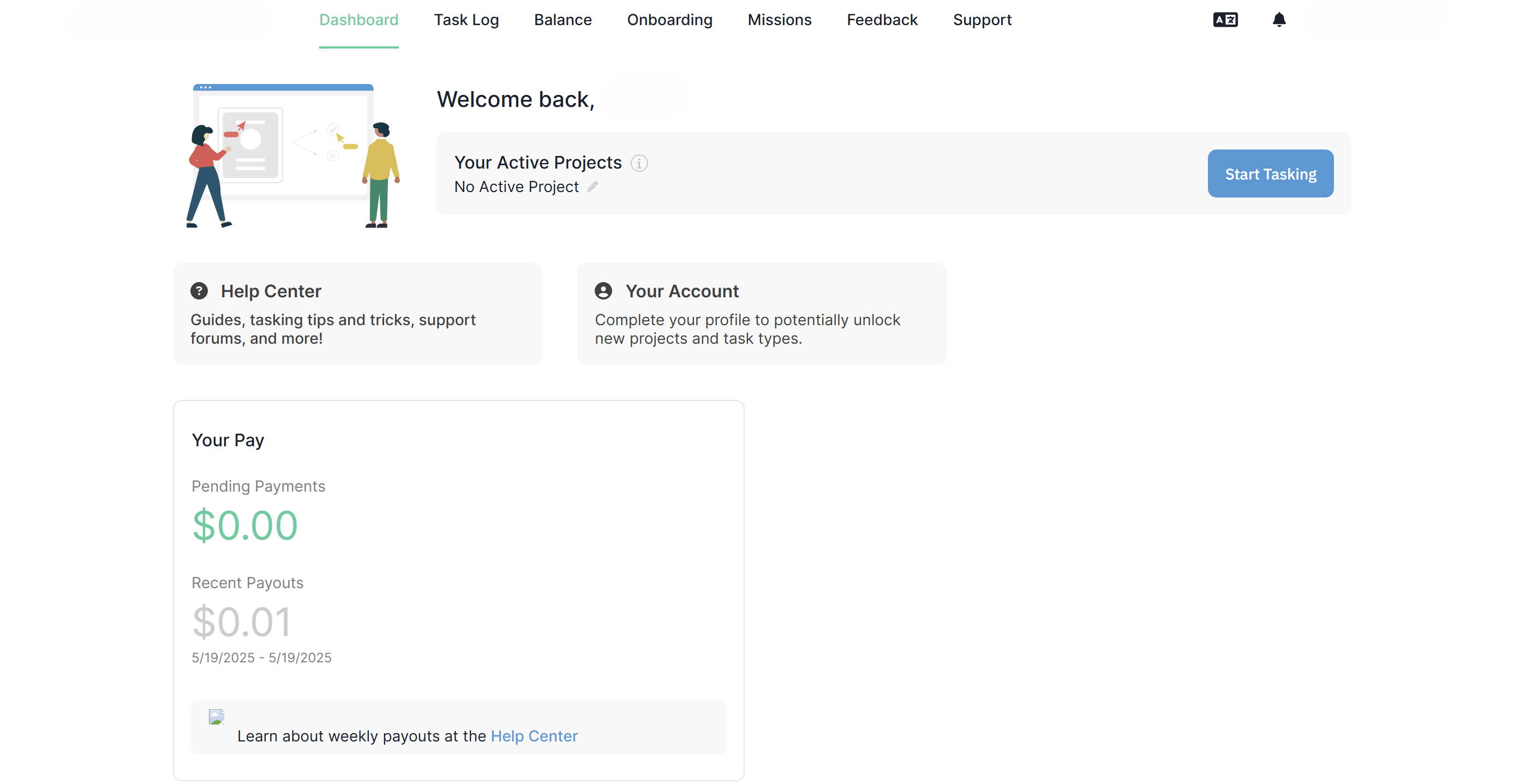

. Image of the starting page after logging in.

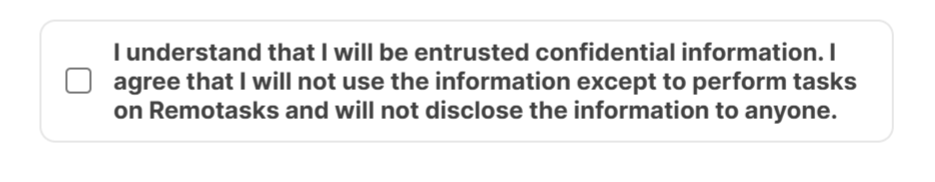

The first thing I had to do was a mandatory security course: “don’t share your password or your task content”. The narrative was focused on keeping your data safe to not risk negative impact for the company (financial and reputation). There was also an information how to make anonymous reports over a whistleblower website – interesting. After that I was asked to sign up to the community forum of this company. Officially, the community is supposed to help you with frequently asked questions and as a place to discuss projects.

Before I could start with a task I had to register a financial connection. The easiest way to do so is by connecting your PayPal account. The reason why PayPal is an often used service for remote and gig work could be investigated more.

Finaly I could start with tasks - or at least I thought so…

Crowdsourcing: Is there an alternative to exploitation?

The idea of crowdsourcing has initially a positive connotation for me. Offering diverse perspectives and maybe helping me to question my assumptions and biases. The same case exists also for research and the development of AI, where crowdsourcing is depicted as “making AI smarter” (and reducing its bias) and commencing a “golden age in survey research” especially since the rise of large crowdsourcing platforms like AMT. 9 However, the rise of those relatively “budget-friendly solutions” also raised some concerns. In her 2018 column Alexandra Samuel asks - after pointing out the benefits of the platforms for research surveys - whether it is ethical for researchers to use platforms like AMT for scientific surveys considering methodological critique and economic injustice. Her answer that follows at the end of her text is straight forward:

“Researchers simply need to deploy a round of test surveys, calculate the actual time to complete each survey, and price their tasks so that their pay rate is at least equivalent to minimum wage.”10

Samuel’s solution is not bad, however in my opinion it ignores both the structural elements of the platforms, and the crowdsourcing systems, based on them, making exploitation possible or even enhancing it.

First of all, as Gray and Suri explain, the system of an hourly based salary economy no longer applies to workers, which are mainly paid by amount of submitted tasks.11 Secondly, I would argue that using an ethical questionable system ethical does not make the system itself more ethical, since it does not change the system but only your individual engagement with it. The goal should be to think on a structural level about possibilities to enable worker communities and data activists to take action, support each other and change the system.

In her new Book Counting Frminicide: Data Feminism in Action Catherine D’Ignazio discusses “participatory design for restorative/transformative data science”. 12 She differs between two ways on how the field of human-computer interaction (HCL) so far tried to engage in political issues. First by individual direct harm reduction and secondly “the support of activists who already taking collective action with digital technologies to combat structural violence”.13 Whereas D’Ignazio agnoliges the benefit of providing direct services to affected individuals, she presents in chapter seven a case study for to support collective activism to combat structural violence/inequality and the possibilities and barriers for research engaging in it. In chapter eight she even offers a toolkit to engage yourself in a project.14 A lecture definitely wort to engage with.

While D’Ignazio focuses on examples of activism concerning gender-related violence, her differentiation of action fits also into the topic of this post. An example for individual direct harm reduction, could be the already mentioned whistleblower hotlines, if working properly. An example of scholarly work in support of collective worker activism on the other hand would be Turkopticon.

Turkopticon was founded by Lilly Irani and Six Silberman. What started as a review website for Turkers (workers of AMT) to share information, developed into a worker-led non-profit organization, advocating for their rights and representing their interests (comparable to union activities). 15 In my opinion one reason why Turkopticon worked well is that they managed to build a worker-led save-space outside of the company platforms, which enable works to act and place demands as a collective.

Workers themselves also connect to each other by themselves. Gray and Suri explore this in a chapter of their book. They show that the global on-demand labor market, mainly on its surface, is looking fractured and that the workers actively engage in community building on their own, even though companies often try to reduce those efforts. When I was conducting my self-experiment, I often gained information from platforms like Youtube and Reddit where workers shared experiences, issues and help, sometimes also because it was not possible over company owned forums. If platforms themselves sometimes intervened in those spaces, I can’t tell.

Gray and Suri suggest platform designers should consider implying collaboration possibilities on platforms. However, what struck me was, that they suggest that platform designers could take control of those collaboration spaces, structuring them and even banning collaboration where it “is working against the desired outcome”.16 And in fact one of the platforms I experienced had its own forum “designed to build discussions and communities. We use […] Forums as a way to share information with you and to help you engage better with the project”. Controlling social spaces by design is what Ruha Benjamin calls “design as a colonizing project, …, to the extent that it is used to describe any and everything.”17 As I would argue this description applies to the forums established by companies and suggested by Gray and Suri. In those forums maybe social connections can be established, but the goal is probably not to build up a worker community like Turkopticon, and the structural power imbalance persist.

Tuesday Night: Coffee and some training experiences

The next night, I sat in my living room with a freshly brewed coffee, ready to take on my first task. But, first a few words on some technical issues I encountered: Since I had virtually relocated myself via VPN to sign-up, the VPN prevented me now from tasking, since it got detected and blocked. However, without it I could access tasks, seemingly not-mattering anymore about my location. I still haven’t figured out what exactly is happening and as we will see it further complicates with individual tasks. One assumption is that some of the individual tasks do not allow VPN, therefore the platform checks for a VPN’s before an account onboards a task.

In any case, I couldn’t begin with tasking right away, as none had been assigned to me (up to this point this situation didn’t change). This might be also connected to my location or just due to the availability of tasks.

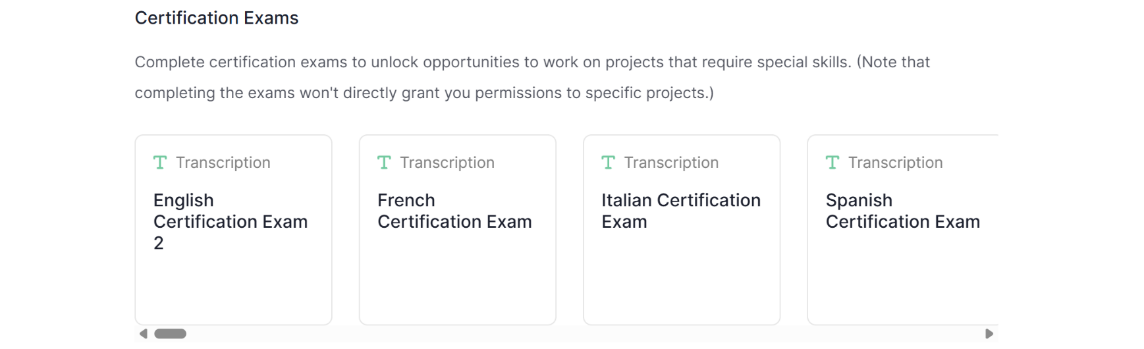

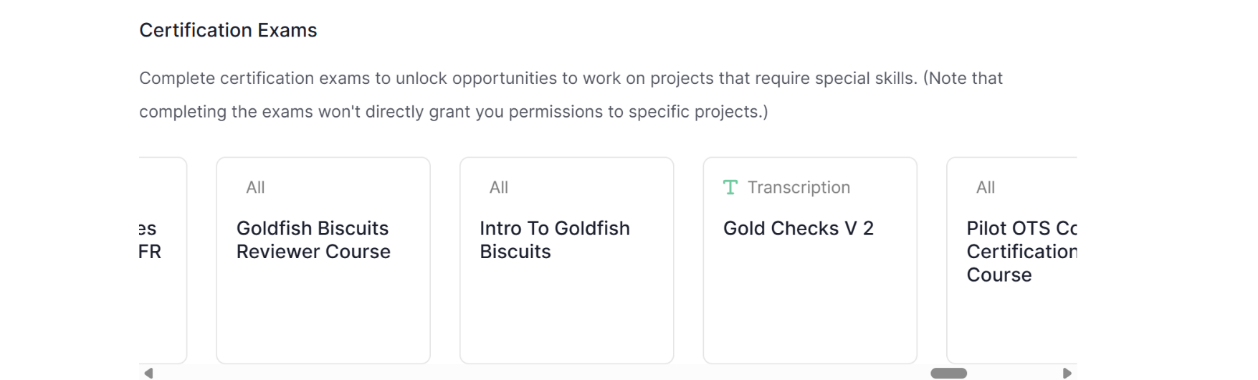

While I assumed that there would be some basic mandatory training to start with, the onboarding section, featured a selection of diverse trainings for individual projects and so-called “certificate tests”, that you can take to qualify for certain projects. Since I didn’t have any projects/tasks to join so far, I decided that I first anyway had to gain some practice, and I started with training.

The tests covered a variety of fields- including transcription tasks in different languages (English, French, Japanese, German etc.), as well as categorization, image segmentation, coding and (image and video) annotation. All of the courses were timed. They even included a course on basic salsa steps, which I failed miserably – was it that the leader does first a step to the front with the left foot, and one to the back with the right one, and then left foot back and right forth, or was it the other way around?

Some of the course material used for training was also from other platforms, like the one that I was redirected to when trying to sign-up.

The transcription tasks were pretty much as expected. You had to complete sentences with the most fitting elements.

Some of the tests were less clear to me, and some I could not initially do, because they were restricted.

Some of the courses were again location-restricted, in this case a virtual relocation could help, if not detected. Others seemed to be inaccessible for different reasons and I could not attempt them. This made it pretty much unpredictable which of the tasks I could actually do.

It also struck me that the difficulty level of the task highly varied. Even for the ones not requiring high language levels, it was necessary to pay close attention to detail.

One task was a review on how to annotate webcam pictures, because the mistake rate seemed to have increased lately. I had to judge images as “good” or “bad” according to specific categories. The categories felt, however, not really intuitive for me. For instance, a bad quality picture, where the hands were not in the lower corner of the picture was judged as “good one” and had to be annotated. An image of good quality, but where the hands were in the lower corner had to be marked as a “bad one” and was not annotated. Other tasks used very specific vocabulary which I first had to look up.

Nevertheless, the following task was one of my favorites:

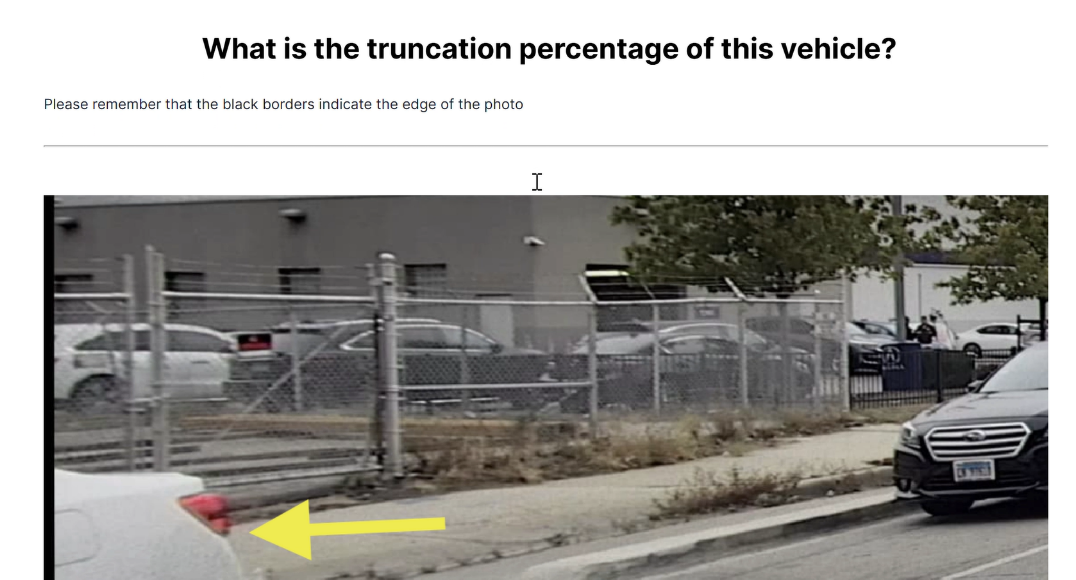

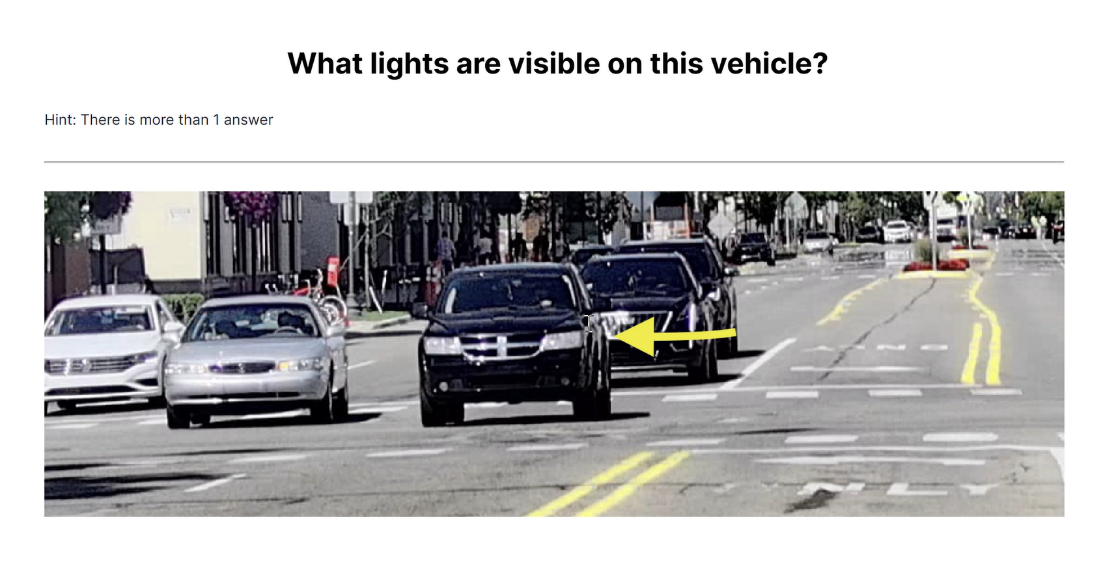

It involved the annotation of data for car cameras. Do you know what truncation means? And how it differs from occlusion? I didn’t- until an AI explained it to me.

The fact that I can’t drive probably didn’t help either.

And I think some answers you just had to know by heart. Or at least I didn’t know how to figure that one out. So maybe it was no surprise that I didn’t pass it.

The training process was sometimes pretty time consuming, but at least, I did learn some things. For example, how LLM’s use meta plans and APIs to answer user requests.

However, it’s crucial to me to remember the my personal conditions conducting this experiment: I am acting out of a privileged position were spending some more time on unpaid training for the sake of experiencing, was somewhat more acceptable.

After experimenting for a few hours with training tasks, I had to pause my experiment for the moment. I am not sure how much more training I would have to do, or if I ever could join a real task. Which likley also depended on the quality of my tasks - I failed a few of them, besides the one already mentioned.

By testing some possible tasks, I gained insight into different human elements in AI training and the narrative training platforms use.

To be honest, I could hardly imagine doing most of the tasks for several hours a day, either as a main job, or as a side hustle, after a full workday. Maybe that would change with more experience. However, what really struck me was, how much human (labor) still seemed to be in the machine.

Resume: What can this post change?

Initially, I planned to be a bit melancholic at this point. I asked myself-as I believe many students and scholars which attempt to bridge scholarly interest and political activism do- will my post have an impact? I think this question is even more important regarding my own privileged position.

As a scholar I think it is important to include my own position in my analysis, regarding the possibilities and limitations of it. Therefore, the goal of this post was not to simulate the experience of exploited workers, ase that is not possible for me. Rather, my post aims to offer a way for (probably) the majority of my readers to encounter the human in the loop of AI and to reflect on the people behind data. I believe this matters in several ways.

As Rafael shows in his paper, there is a usage inequality of AI: It is primarily used in the Global North; while the consequences -ecological, social and economic- are mainly felt in the Global South. One example, is the exploitive labor system of remote data annotation, which often operates in a classical extractive way: labor and profit is extracted. Though the situation is complex upon looking closer at it- not all remote labor has to be exploitive- however most platforms posses the systematic potential to be. And as long as this potential remains, I believe it is worth thinking about our use of data and striving for collective and systematic solutions, as D’Inazio presents in her studies.

As more and more people in Europe support supply chain regulations, perhabs we could also think about data supply regulations - without further marginalizing and precarizing people in volatile situations, as can happen if companies simply restrict work from locations instead of improving labor conditions. To think about the humans in the or behind the machine is also important for people who already try to debias AI. Experiencing data annotation - and its system based on hyper-division and repetition- may help to gain a different perspective of the foundation of machine learning and where changes could be applied.

In this way, this post may help to better understand the machine, rather than the humans behind it. While showing, that it is our responsibility to emphasize and stand in solidarity with the workers behind every AI- even if they are consciously been made invisible, and even if we unconsciously may not think at first about them.

Literature

Benjamin, Ruth. Race after Technology. Abolition Tools for the New Jim Code, 2019.

Brandom, Russell. Scale AI’s Remotasks platform is dropping whole countries without explanation, in: Rest of the World, 28.03.2024. https://restofworld.org/2024/scale-ai-remotasks-banned-workers/, accessed 23.05,2025.

D’Ignazio, Catherine. Book Counting Frminicide: Data Feminism in Action, 2024

D’Ignazio, Catherine. Counting Feminicide: Data Feminism in Action. The MIT Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14671.001.0001.

Gray, Mary L. and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work. How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, 2019.

Reffell, Clive: Why is Crowdsourcing Vital to Make AI Smarter? On The Crowdsourcing Week, no publishing date. Online: https://crowdsourcingweek.com/blog/crowdsourcing-makes-ai-smarter/

Samuel, Alexandra. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk has Reinvented Research, in: The Digital Voyage, 15.03.2018.Online: https://daily.jstor.org/amazons-mechanical-turk-has-reinvented-research/

Simon, Théophile. Die Zwansarbeiter*innen hinter der Künstlichen Intelligenz, Amnesty-Magazin März 2024. Online: https://www.amnesty.ch/de/ueber-amnesty/publikationen/magazin-amnesty/2024-1/die-zwangsarbeiter-innen-hinter-der-kuenstlichen-intelligenz

Irani, Lilly, Silberman, Six and AMT Workers: Turkopticon https://turkopticon.net/

Footnotes

Request made on 22 May 2025, using the free version of GPT-4.1 mini model without login. Exact prompt: “Can you be sure that there was no labor exploitation regarding the annotation of your training data?”↩︎

Théophile Simon, Die Zwansarbeiter*innen hinter der Künstlichen Intelligenz, Amnesty-Magazin März 2024. Online: https://www.amnesty.ch/de/ueber-amnesty/publikationen/magazin-amnesty/2024-1/die-zwangsarbeiter-innen-hinter-der-kuenstlichen-intelligenz↩︎

Brandom, Russell. Scale AI’s Remotasks platform is dropping whole countries without explanation, in:

Rest of the World, 28.03.2024. https://restofworld.org/2024/scale-ai-remotasks-banned-workers/, accessed 23.05,2025.↩︎

Remotask Working Location Policy, last updated Feb 14, 2023, last accessed 25.05.205.↩︎

EU Artificiel Intelligence Act, https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/, last accessed 19.05.2025.↩︎

Théophile Simon, Die Zwangsarbeiter*innen hinter der Künstlichen Intelligenz, Amnesty-Magazin März 2024. Online: https://www.amnesty.ch/de/ueber-amnesty/publikationen/magazin-amnesty/2024-1/die-zwangsarbeiter-innen-hinter-der-kuenstlichen-intelligenz↩︎

Gray, Mary L. and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work. How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, 2019, S.85-93.↩︎

See e.g. Mitratech Syntrio, online: https://syntrio.com/resources/mitratech-reporting-hotlines-overview/, last accessed 26.05.2025.↩︎

See for example and Reffell, Clive: Why is Crowdsourcing Vital to Make AI Smarter? On The Crowdsourcing Week, no publishing date. Online: https://crowdsourcingweek.com/blog/crowdsourcing-makes-ai-smarter/, last accessed: 18.05.2025.

Samuel, Alexandra. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk has Reinvented Research, in: The Digital Voyage, 15.03.2018.Online: https://daily.jstor.org/amazons-mechanical-turk-has-reinvented-research/↩︎

Samuel, Alexandra. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk has Reinvented Research.↩︎

Gray, Mary L. and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work. How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, 2019, S.121-39.↩︎

Catherine D’Ignazio, Counting Frminicide: Data Feminism in Action, 2024, p.214.↩︎

Catherine D’Ignazio, Counting Frminicide: Data Feminism in Action, 2024, p.220f.↩︎

Same, chapter 7 and 8.↩︎

See https://turkopticon.net/, last accessed 21.05.2025.↩︎

Gray, Mary L. and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work. How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, 2019. P.138.↩︎

Benjamin, Ruth. Race after Technology. Abolition Tools for the New Jim Code, 2019, p.60-97.↩︎